BEAUTY AND TRUTH

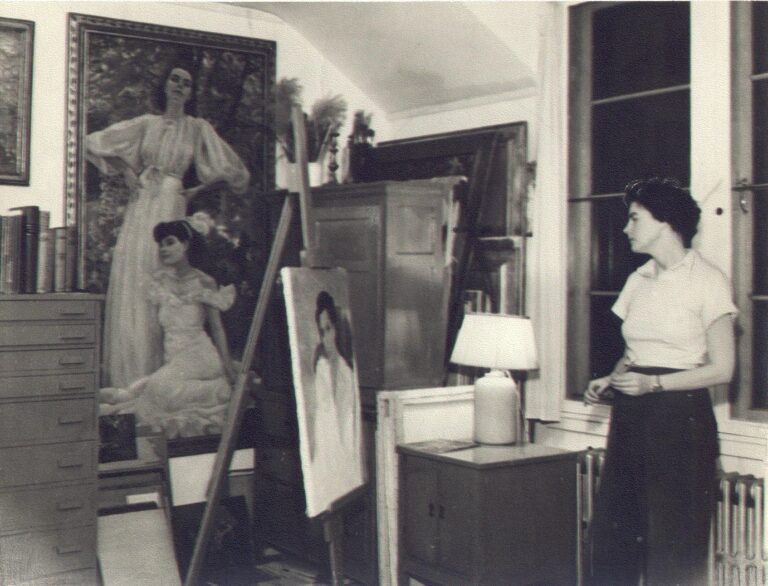

Last week was the anniversary of my mother, the artist Marie Cecilia Guard’s, birthday, which brought me back to appreciating her lifelong pursuit of beauty and her unfailing dedication to mastering her art.

As the daughter of professional Canadian artist parents who shared a lifelong passion for art, [see also my father Ken Phillips’ website] I grew up breathing in the fragrance of oil paints and turpentine and surrounded by images.

Long ago, my mother told me that her wish to become a figure artist began when she was thirteen and her own mother gave her a book about Raphael and his paintings. The intertwining composition of The Three Graces haunted her, she said. Later, when she saw a full-sized reproduction of Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus in a downtown Toronto department store window, she was lastingly captivated by the idea that she too could create large-scale paintings.

She studied at what was then The Ontario College of Art, with Group of Seven teachers, including her favorite J.E.H. Macdonald, under whose supervision she took a post-graduate year. She was taught there to search for a truth and beauty which lies behind appearance and which begins with a knowledge of structure.

Her quest for the fundamentals of design, along with the deepest essence of her subject required a return to studying the nude. (Later, when I asked her why many of her subjects were nudes, she recommended Kenneth Clark’s The Nude. But if pressed, she paraphrased Matisse:

[What]I am after above all is expression. What interests me most is neither still life nor landscape, but the human figure. It is that which best permits me to express my almost religious awe towards life.

During the thirties, young Marie’s pictures became astonishing. Frequently life-sized or more, these portraits and figure studies in oil were suffused with light; they reflected a radiant sense of possibility and promise. Throughout this period, while still in her own thirties, my mother’s nudes revealed eros, harmony, energy and ecstasy. She examined women in many aspects: closed and remote (as in Idyl, her back view of the nude draped in chrysanthemums), or open and daring, (a figure with a background of flamelike poppies, painted with an almost glaring boldness, and with her arms folded defiantly behind her head, challenging the viewer with a direct stare.) In keeping with her classical upbringing, these were women larger than life, women as goddesses. This was work that obeyed Renoir’s challenge: “Paint with joy, with the same joy with which you make love.” Frequently, her paintings were exhibited in Toronto’s prestigious O.C.A and R.S.A. shows.

Unfortunately, during the war years, and even into the sixties, censorship became a problem in Toronto. What was more, largely because too many paintings of pompous dignitaries had been submitted to the important shows, portraits in general were banned from the exhibitions. Moreover, even in the new house they built in what is now Mississauga, there was little storage room for such large canvases. For many reasons, my mother’s exhibition career largely came to a halt. By now crippled by arthritis, and shut off from Toronto and her friends and teachers by wartime gas rationing, my mother faced the challenges of raising two lively, disruptive daughters with very little money.

Still, in spite of her troubles, my mother maintained her spirit and determination lifelong. Until her last days, in her nineties, she drew always and often continued to make watercolor studies. While I was a child, my experience was of sketches of the gestures made by birds and squirrels, glimpsed through the windows, or of the swaying pines which hovered over our house. These images lay on tables as an invitation for her to keep going. To a daughter watching, it was as if she couldn’t make sense of her world without drawing. (Even shopping lists were blended with studies of the curving line of an antique chair back, or a child’s hands.) Her small, metal case of paints was always at the ready–just in case. And when she could, she continued learning from books and exhibitions, always open to the work of artists such as Henry Moore, or the German Kaethe Kollwitz.

In 1957 she painted in oil one further, defiantly whimsical, but symbolic nude. This was Caprice (35″ X 25″)–a blithe figure in warmest flesh tones, stepping lightly through a forest world of newly fallen snow. Beauty created in a cold climate.

As I was growing up, Marie turned to portraits, some commissioned, and some of her two daughters.

But no matter how difficult and painful her life, there was always beauty. More than once when I was a teenager she quoted from Keats” Ode on a Grecian Urn,

Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.

Always, by living beautifully, in spite of sometimes searing pain, all the time living with profound appreciation, what my mother instilled in me was a lifelong reverence.