ABOUT SMALL, WITH GREAT LOVE

I’m sorry to have been irregular here lately. I’ve decided that I need to spend the summer focusing on my memoir about a girl with artist parents growing up in a woods. But I miss writing to you. Already the topics are piling up. I look forward to returning in September. Please hold space for me.

The Hill of Summer

Imagine that we are sitting together in a loose circle, shaded by one of the generous hillside maples of Singing Meadow. Here, we are sheltered from the blazing July heat which is rising from the wetland below us.

I want to talk to you about J.A. Baker (1926–1987), one of my favorite British nature writers, and specially about his book, The Hill of Summer.

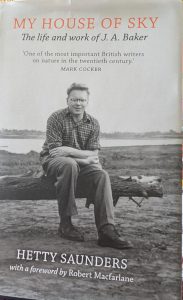

According to Mark Cocker, Baker is now widely acknowledged as one of the most important British nature writers of the twentieth century. But as so often is the case, that recognition was a long time coming.

In the early seventies, I discovered Baker’s first, and best-known book,  The Peregrine, in Vermont’s welcoming Middlebury Vermont Bookstore. I took it back to our campsite high in the Green Mountains. Sitting under the canopy we had set up to shelter our picnic table, I only meant to have a quick glance. But instead, I found that I couldn’t stop reading. I was shocked by the truth of his prose. Think of Ted Hughes, one of the poets he admired. Supper was late, organizing small boys to go to get washed before it was time for campfire was completely forgotten. This unknown English nature writer spoke to my heart with his powerful prose. Right away I saw it as close to poetry like that of Gerard Manly Hopkins and Dylan Thomas.

The Peregrine, in Vermont’s welcoming Middlebury Vermont Bookstore. I took it back to our campsite high in the Green Mountains. Sitting under the canopy we had set up to shelter our picnic table, I only meant to have a quick glance. But instead, I found that I couldn’t stop reading. I was shocked by the truth of his prose. Think of Ted Hughes, one of the poets he admired. Supper was late, organizing small boys to go to get washed before it was time for campfire was completely forgotten. This unknown English nature writer spoke to my heart with his powerful prose. Right away I saw it as close to poetry like that of Gerard Manly Hopkins and Dylan Thomas.

Listen:

Fear grew like a fungus upon the green surface of the woodland air.

And:

The huge and glittering headlands of slate rise slowly from the sea, like defaced idols. The rocks of the shore appear, with the white waves towering above them. A falcon dashes away from the rocks, hurling low across the surface of the sea. It is a merlin, an adult male, shining blue in the sunlight. Far above him, and a hundred yards in front, a flock of ringed plover is flying, like a net of gleaming stars. The merlin dips and sways above the water, light and swift as the tongue of a snake. He whips away great spans of air with sharp wings that quiver up and down like flickering spokes. He flies faster, springing and leaping forward, his wings shimmering as though they were beneath the surface of the water. I can see only the glitter of their vibration.

In Cocker’s words, “The Peregrine is distinguished by its close focus on one species, the fastest-flying bird on Earth.” But at the time of Baker’s observations, this falcon was so stricken by the toxic effects of organochlorine-based agrochemicals that it was threatened with extinction. “It was that anxiety which charged Baker with his deep sense of mission as he tracked the falcons across the wintry landscapes of Essex. ‘For ten years I followed the peregrine’, he wrote, ‘I was possessed by it. It was a grail for me. Now it has gone.’ This sense of the bird’s impending doom supplies the book, not only with its emotional rationale, but also its thematic unity and burning narrative drive.” (Baker, J. A. The Peregrine: The Hill of Summer & Diaries: The Complete Works of J. A. Baker. HarperCollins Publishers.

All his short life Baker lived in Essex in what was then the small town of Chelmsford. Surprisingly, although it was less than an hour from London in his days his surroundings at that time were rural. Sensitive and high strung, he was described by his wife and his editor as a natural loner. Because he never learned to drive, all his passionate, obsessive observation of the land and birds near that town was done by bicycle. But in time, these solitary excursions were made harder because of the increasing crippling he suffered from rheumatic arthritis, and at just 61 he died from cancer.

As his journals show, he read voraciously, particularly the poets. His poetry collections included Wordsworth, Keats, Byron, Shelley, Tennyson, Hardy, Eliot, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Edward Thomas, Pablo Neruda, Seamus Heaney, and Ted Hughes. His letters reveal that he admired Dylan Thomas’ poetry, particularly Fern Hill.

Now, we ourselves are just past our own summer’s crest, but we still are deeply immersed in it. Although we are beyond the fervor of spring birdsong, below us you will hear the common yellowthroat’s insistent, “Oh witchetty, witchetty” and the American goldfinches, skipping over the plain below, while above us the wind stirs in the maple leaves.

Most important to me was the link Baker forged between prose and poetry. This has been the direction I have aimed for with my own writing. Of course I searched out and bought Baker’s later book, The Hill of Summer (1969), and this is what I want to talk about today.

In its time, Baker’s later book (he wrote only two) was considered a disappointing follow up to The Peregrine and it has never received the appreciation I believe it deserves. The biggest objection seems to be that it is lacking plot. Who accused Gilbert White’s journals of lacking plot? Writers like Mark Cocker object that its “more difficult and elusive text” … lacks “the emotional rationale” and the “burning narrative drive” of The Peregrine.

But I see this book, as a journey through a Sussex spring, summer and fall where each chapter gives you a separate habitat, as prose poetry which is evocative of Baker’s home ground and daring in its expression. To me, it is reminiscent of the poet John Clare.

Although occasionally I find Baker’s writing excessive, like eating rich pastry, and as Cocker noted, certainly it is dense, but then, most often so is poetry. The Hill of Summer is a book I need to touch base with every summer.

Listen:

“But the silence compels. It is very old silence. It seems to have been sinking slowly down through the sky for numberless centuries, like the slow fall of the chalk through the clear Cretaceous sea. It has settled deep. We are under it now, we are possessed by it. When strangers come here, many will say, ‘It’s flat. There is nothing here’. And they will go away again. But there is something here, something more than the thousands of birds and insects, than the millions of marine creatures. The wilderness is here. To me the wilderness is not a place. It is the indefinable essence or spirit that lives in a place, as shadowy as the archetype of a dream, but real, and recognizable. It lives where it can find refuge, fugitive, fearful as a deer. It is rare now. Man is killing the wilderness, hunting it down. On the east coast of England, this is perhaps its last home. Once gone, it will be gone forever.”

In Hetty Saunders’ recent fine biography, My House of Sky: the life and work of J.A. Baker she writes that:

In Hetty Saunders’ recent fine biography, My House of Sky: the life and work of J.A. Baker she writes that:

After the end of the Second World War, Baker told Donald Samuel what he considered the purpose of the author to be. ‘It seems to me,’ he wrote, ‘that, in the view of the world’s condition today, we who have creative ambitions and, perhaps, a genuine creative ability, are bound by our conscience to give all that we have to the cause of working for a better way of living.’ SURELY THOSE WORDS ARE TRUER NOW THAN EVER.