Ken in the Wilderness

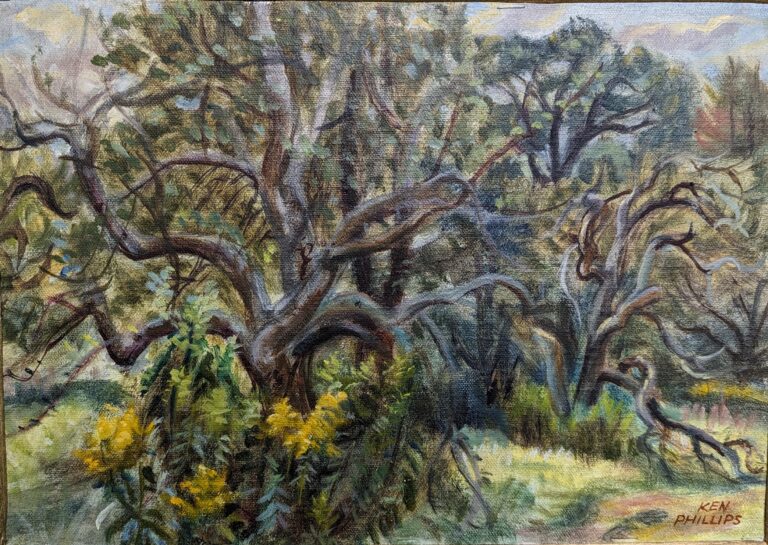

This week, I spent a morning revisiting my artist father, Ken Phillips’, Ruined Orchard series of oil sketches.

As I looked, I could see how it was for him then.

When he set out that September morning to the dying orchard, my father would have been heading deep into his own wilderness of despair. Just as it was the for the ragged trees he planned to draw, his art career had withered. After studying with Group of Seven teachers at the College of Art, [Ontario College of Art & Design University], including his beloved Arthur Lismer, his paintings were exhibited and praised in the most prestigious Toronto shows. He had begun with every reason to hope that he would be able to share his joy in art. Sadly, after the Second World War, tastes changed, and his luck turned against him. Wryly he would quote the old song: I brought my harp to the party, but nobody asked me to play.

Almost worse were the many hours that he had spent earning a small living in Art Advertising at the Simpsons department store on Queen Street. All those years, using his precious craft purely to earn a living drawing mattresses and refrigerators. All that time having to deny his urgent need to do his heart’s work. Longing to follow the irrepressible line. To chase joy. To live in a rapture of light. And always to give his love forward.

In many ways his life had been soul murder. But, true to the old Latin motto nulla dies sine linea, he never, ever quit making art every day.

**

All his adult life he had to sell his heart. Yet nevertheless he also was saving whatever he could. Whatever way he could. Perhaps that is a large, impossible part of art: to salvage.

In the fifties, when his city was being torn apart he spent his extended noon hours recording the destruction. First he drew the old China Town, which was being pulled down before a new city hall could be built. While his felt pen whipped over his drawing board, he also was making friends, as he always did, being invited to share lunch with the workmen. The reaching out. He couldn’t help himself. As well as his drawings, he gathered souvenirs–the counters of an ivory mah jong set, several of the white and blue earthenware tea kettles.

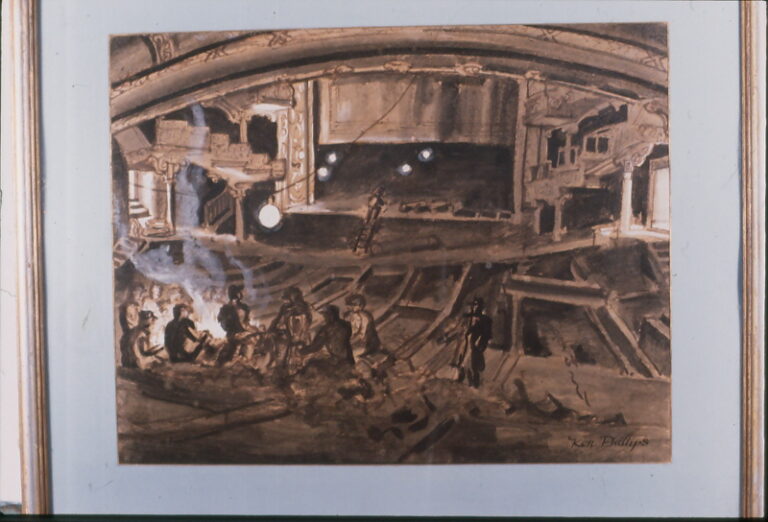

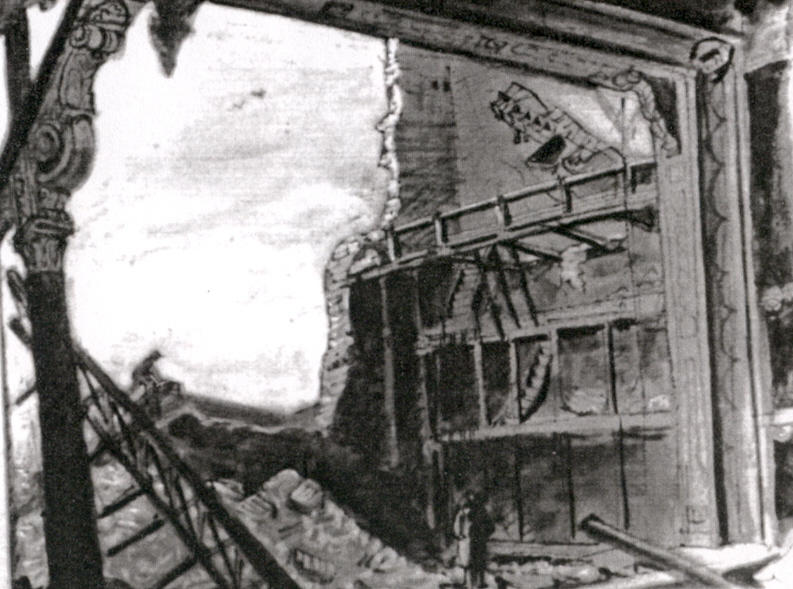

Some of his most compelling work came about after he learned that his beloved queens, the downtown vaudeville theatres also were to be torn down. Art was theatre too. He knew that in his very bones. Every noon hour his pen whistled across his board as he captured the dismantling of the plaster ornaments–cherubs, Pan, the crashing prosceniums, now all rubble. Gashes laid open the stages which once had been alive with magic.

**

So, on that morning a decade later, when he set out, he was dazed and afraid. After all those years of constrictions, soon he would be taking his last trip on the commuter train. Of course, he had seized the unexpected chance to retire early. His heart’s desire. Now, at last, my artist father would be coming home to stay. It should have been a blessing. And truly he loved his home woods. But it would turn out that he fed off his city with a Dickensian glee, the quirkiness of buildings, streets alive with the people he captured in quick sketches–gossips wheeling baby prams, old men hunched over their cards in Grange Park. There were weeks of stalking clouds in the small red-covered notebooks he always kept ready in his shirt pocket. Or maybe just hands. A page of hands.

On that September morning, at sixty-three, and with a failing heart, once again my father would have taken his sketch box and tramped through the rough field grass to mourn a different scene. At the end of the street there was a dying orchard. He knew that before the snow fell, the ragged, tall apple trees would be ripped out, preparing the land for yet another subdivision.

One night he came to me with tears in his eyes. He had just read that on the celebrated Japanese print-maker’s Hokusai’s gravestone was engraved Old Man Mad About Painting. That was him! Then, one June night when he was 73, his heart was torn open by a massive heart attack.

At first I was wracked by grief, knowing that he had died alone, believing that he had failed in what he so loved. E.M. Forster’s Only connect had been his favorite motto and he had failed.

And yet. And yet…

There had been a counterpoint to his urgent need for privacy, and that was a fervent love of people. Astonishingly, it had turned out that, no matter how clumsily he expressed this, they understood. Most of all, always, he was putting his arm on your sleeve, gesturing sweepingly– “Look. Only look…”

As a teenager I was vaguely aware of, and sometimes embarrassed by, his extraordinary reaching out. When he rushed up to a pianist after a Schuman concert to humbly express the joy his performance had given him, I wanted to writhe and hide under my chair. But astonishingly, the pianist caught the appreciation and lingered on the stage to talk.

Later, when he started his brief yearly trips to England, in his letters home he wrote of how he made lasting friends with the vendors at Petticoat Lane, with amateur actors who wrote him every year at Christmas about their stage experiences. Somehow, he made connection with everyone from workmen sharing their lunch, to the Dean of Westminster, who ordered a chair to be brought out for him so he could draw in comfort, and who popped out between meetings to talk about their shared passion for architecture and art. When he sketched elephants in the parking lot outside the travelling Circus Vargas, the artistes invited him into their trailers and later sent him yearly postcards from their winter quarters in Florida. Come join us! You’d be very welcome. He was invited to tea at the country home of Allan Burton, then Chairman of his employer Simpson’s, and eventually he encouraged Burton to use his own sketches for the yearly Christmas cards he sent to family and friends. But he had equal affection for the trainmen with whom he hung out in their snug caboose sanctuary. He truly cared about all of them. At our kitchen table he brushed tears from his eyes when he recounted how a stockbroker friend had told him he was divorcing his wife.

**

Who knows?

I am left with intimations of a different kind of connection, a different kind of success. One evening shortly before his retirement, I went back to my old woodland home with him on the commuter train to spend a weekend. Everyone is in a hurry to catch the train home, but somehow people keep breaking ranks from the pressing crowds and grabbing him, “Kenny”. It is astonishing. They are happy for him that he has his grown-up daughter with him. Rushing as he is, he would like to tell me a bit about each one. But that is impossible with an overwhelming fifty people crowding up to greet him on the platform, or to hold up the procession squeezing along the aisle of the train car, just to touch him or share a quick joke .

I drink in those moments, while, bemused, unassuming, privately intent on securing his window, the one with the seat facing forward, my father settles in, whips out his specially whittled pencil and the little red notebook which fit exactly into his shirt pocket and prepares to capture blowing smoke.