ADHD and the Pursuit of Smallness

Before I share more stories about the many passions which brighten my days, I want to explain how lifechanging it has been for me to understand the new thinking on ADHD. (I’m writing this in hopes that it might resonate for you, or for some of those you love.)

If only I had been able read them, there have been so many indicators of this condition in my lifelong disappointing behavior. Unfortunately, it has taken me until now, in my seventies, to learn that ADHD covers much more than the familiar hyperactive behaviour, which, it turns out, is mostly manifested in males.

Discovering psychiatrist Edward M. Hallowell’s excellent Driven to Distraction: Recognizing and Coping With Attention Deficit Disorder (https://drhallowell.com/), now followed up by: ADHD 2.0 New Science and Essential Strategies for Thriving With Distraction—from Childhood through Adulthood has been life-changing for me. Not only has it helped me to work with my problems but also to celebrate what I appreciate as gifts.

There now is much exciting new research into the manifestations and treatment of the disorder, but I have found Dr. Hallowell’s clear, compassionate writing on ADHD particularly helpful. The psychiatrist, who himself has this condition, explains:

‘ADHD’ is a term that describes a way of being in the world. It is neither entirely a disorder nor entirely an asset. It is an array of traits specific to a unique kind of mind. It can become a distinct advantage or an abiding curse, depending on how a person manages it.”

Hallowell, Edward M.; Ratey, John J.. ADHD 2.0: New Science and Essential Strategies for Thriving with Distraction–from Childhood through Adulthood (p. 128). Random House Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

If I were telling you about me, I might start by saying that I am a fantastic idea person. Ask me about almost anything and I will spray out ideas until I see your eyes glaze over. “Well, what about?” “You could try?” “Maybe you should look at.” “There’s another aspect to be considered.” Fortunately for you, though, long experience has taught me when it’s time to be quiet.

What I have found most helpful is Hallowell’s explanation:

A person with ADHD has the power of a Ferrari engine but with bicycle-strength brakes. It’s the mismatch of engine power to braking capability that causes the problems. Strengthening one’s brakes is the name of the game.[my emphasis]

The main reason I’m writing about my new understanding of my “way of being in the world” is that eventually I want to tell you about some of my interests: my life in nature, weaving, spinning, hooking rugs, knitting, quilting, playing piano, philosophy, and oh so much more. At this point, you might say admiringly: “Wow, so many…” But alternatively you might well point out that I promised a blog about the beauty of smallness. At which point I would have to concede that if this array of interests is my delight, it also is my challenge. It certainly has nothing to do with simplicity.

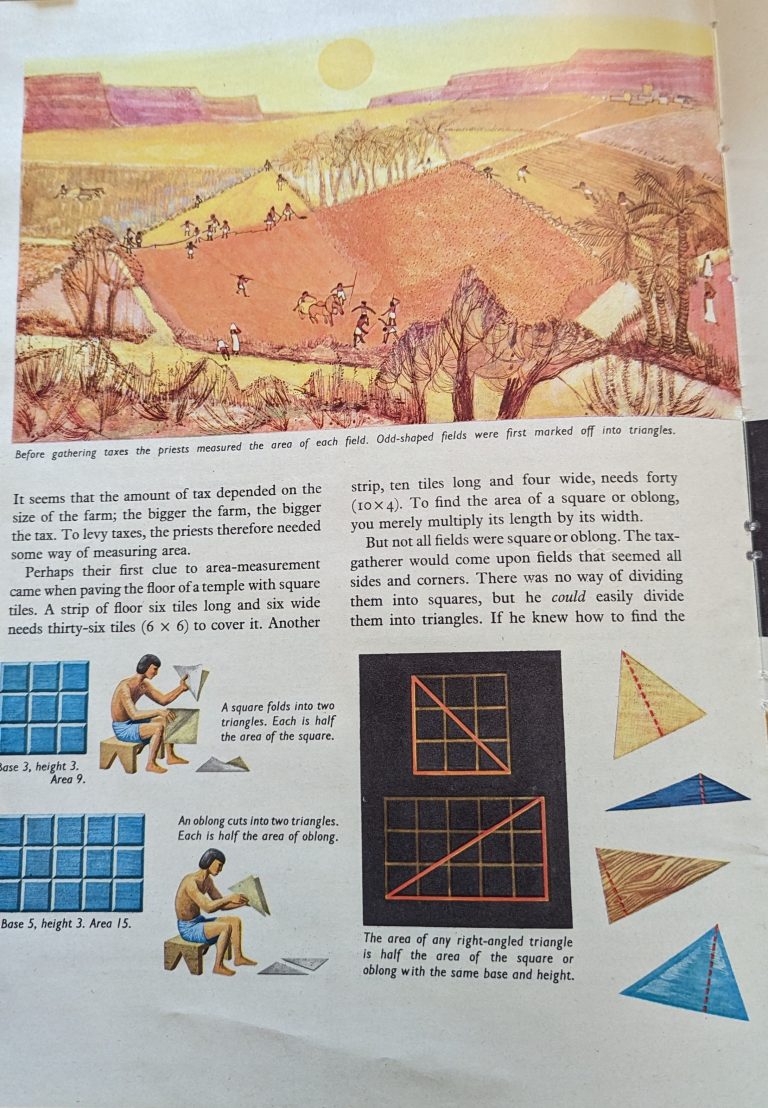

Here’s an example. In Grade Ten my High School principal made me a deal. Based on my disappointing performance in Geometry, he agreed to give me a bare pass if I promised never to sign up for any Math course again. As always, my main problem was focus. Here’s a sample of how my method of thinking always tripped me up. Full of determination, I would set out to solve a proposition. I turned to that afternoon’s interesting, might I say beautiful, triangle.

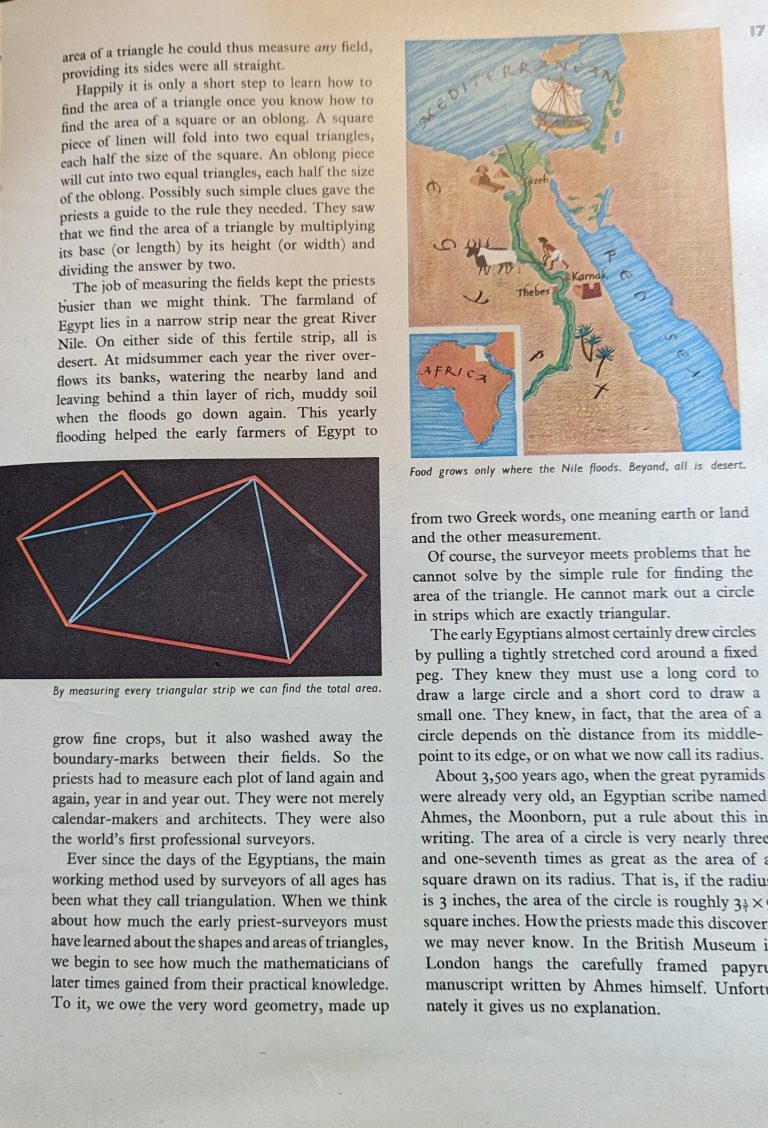

But then came a big sidetrack to the general idea of triangles, and the pictures my father, always an ardent abettor of sidetrack, recently had showed me in Lancelot Hogben’s outstanding introduction to math, The Wonderful World of Mathematics.

And that was all I needed for me to become lost. First, I reflected on the source of the Hogben book, the excellent Toronto Boys and Girls’ Library. Then my brain yanked me back on track, sort of: Egypt, the role of triangles in the lives of Egyptians, the stark beauty of the desert themes. How did the bleak simplicity of the landscape compare with the even plainer diagram in my black and white textbook?

The pacing teacher turned into my aisle. Ok, fine. I backtracked again to check back to the explanation of the proposition. But inevitably this led to more sidetracks about potential alternative ways of understanding the properties of triangles. So. I understood that much. But somewhere on the way to the version I was invited to solve that day, my dancing brain leapt sideways and forward. The ruled notebook page with my solution remained blank. Well, you get the picture. Or maybe not. (I rather hope you don’t.)

Forever underachieving, falling behind, and feeling ashamed about it, I grew up trying to fit in, hiding my general incompetence. This meant that I learned work arounds so that nobody noticed my short-comings much. Somehow I slithered through high school and most of university on sheer audacity. Desperately bored in English, and outraged at the awfulness of parsing my beloved Jane Austen line by line, I made up imaginary books for book reviews and read French novels by holding them on my knees under the desk so I could ignore the teacher’s irrelevance. If I simply couldn’t produce a single date for a history test, boy could I blather my way through the essay questions. I also learned not to plaster my many excellent, if often unwelcome ideas around so freely.

Unfortunately, I still grew up with reproachful voices, my own, my parents’, my teachers’: “What is wrong with you? You should take pride in your work.” “Why is it that you never remember?” “Couldn’t you try a bit harder?” “If you cared you could do better?” “Why is someone who loves books such a slow reader?” “But what did I just tell you? Peri. Aren’t you listening to me?” The contempt and constant suggestions that my lack of compliance was my fault, or that I was stupid (which I honestly didn’t think I was) hurt terribly. I was deeply ashamed. Honestly, I rarely wanted to be disobedient. I wanted to do well. Clearly I was simply never good enough. Reading Hallowell and Ratey‘s ADHD 2.0, I found research suggesting people with this condition could lose as many as 13 years of an average life. In retrospect I think that may have been true for me.

However, as the authors define it ‘ADHD’ is a term that describes a way of being in the world. It is neither entirely a disorder nor entirely an asset. It is an array of traits specific to a unique kind of mind. It can become a distinct advantage or an abiding curse, depending on how a person manages it. Somehow I learned to live well in spite of my challenges. In fact, in the main I love my dancing, imaginative mind, and the gateway into creative thinking which it gives me. All the same, it also is clear that I could be a better version of myself if I could develop Hallowell’s Ferrari brakes, i.e. better control over my overactive mind.

Managing my version of ADHD has taught me patience, and, now, thanks to the new scientific discoveries about it I also am learning strategies which help me cope with my galloping attention.

- Simple awareness of my goals and when the patterns of my thinking go off the rails helps.

- When I need to be single-minded, David Allen’s helpful, best-selling Getting Things Done, the art of stress-free productivity also helps. I use all the tricks–highlighting, post-it notes, a daybook with side-notes, pop-up reminders on my computer.

- Setting smaller, achievable goals is useful.

- Finding my ridiculous mind funny as well as problematic also makes a difference.

- When I get snarled up in excessive dreaming, it’s important to remember to just keep going. (Keeping going could be: walking down the lane to visit my favorite pine, 10 minutes of breathing exercises, walking around the house annoying my cats by singing, tidying papers on my desk (a special treat I save for just these moments), laying out all the ingredients for the muffins I will cook later, so they’ll come together quickly after I’m done work, giving a neighbor a quick call to make sure he’s well

- Conversely, when I stall from overload, as I so often do, I am learning to accept how important it is to allow myself more breathing room.

- Most important of all for me is how freeing it is to lose the lifelong, crippling weight of self-blame.

**Unfortunately, there is no room here to mention more of the exciting new findings about how balance exercises can improve focus; about the confusing ability to occasionally superfocus, and about how “the ADHD mind recoils from boredom, disappearing into a fervent search for stimulation”.

A Few of My Interests