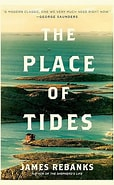

The Place of Tides

In acclaimed farmer/author, James Rebanks’ previous best-selling books, [The Shepherd’s Life and Pastoral Song] he told of how our rural landscapes and age-old wisdom have been brought almost to a final destruction.

With his new book, The Place of Tides, he writes again of these profound concerns, of what to make of our highly damaged life, both physically and personally, but in a more intimate, brave way.

he writes again of these profound concerns, of what to make of our highly damaged life, both physically and personally, but in a more intimate, brave way.

I was touched to my core by this compelling, finely written book. Not only does The Place of Tides give us a wisdom path told through story, but it also surrounds us in the beauty of an exceptional place, a lonely Norwegian island.

At home in the Lake District, Rebank’s elders, the people he had looked to for guidance, had died and he found himself feeling unmoored, like a piece of timber drifting on the current. Tired and lost, as I, and so many of us are, he was fighting despair.

He writes:

I felt overwhelmed, and angry at everyone around me. I was in trouble, and I didn’t know what to do about it.

Some years ago, on a research project in Norway, he had met Anna, who husbanded the eider ducks on a wild island each spring, collecting the down with which they lined their nests for duvets. Now, in his time of personal despair, he kept remembering the old woman on the rocks. There was something still alive in her that had died in me. And so, to his own surprise, he asked Anna if he could join her and her helper friend, Ingrid, for what would be the last time she followed the life she had lived each spring for many years.

Although she assented dubiously to accept him as a helper and observer, for the first bleak, wintry weeks there was doubt about whether she would make it through this, her last intended year on the island. At first, her health was so shaky that it was uncertain. As for Rebanks, he was homesick for his farm, wife, and four children and in this remarkable, but unfamiliar island setting, he felt more lost than ever.

But, the island was a place where life and earth were close neighbours

and gradually, inspired by her chosen life there, Anna regained her strength. As for the author, reduced to simplicity, he discovered that he felt affirmed by working side by side for many hours on the same tasks. As he would have been with the age-old excitement of lambing time at home in the Lake District, Rebanks came to appreciate how necessary it was for the old woman to continue to be working at her meaningful, chosen work, the work psychologist Viktor Frankl prescribed for us all.

In his resting moments, Rebanks turned to Homer, seeing life on the island in the way of a story teller:

These first weeks of nesting, as the ducks were coming ashore and gathering around the house, made Anna seem almost mystical. It was like she had somehow called them in from the open ocean to her voice and her gentle, stroking hands. The ducks seemed enchanted by her, unafraid. …

Rarely have I seen anyone so absorbed in each living moment. I began to understand the old Norwegian myths about the rocks and mountains coming alive, shapeshifting into creatures that were half human and half geology. This way of living demanded a loss of self, a surrendering to the rocks, rain, wind, and tides.

Anna reminded me that the first rule of living is to live. To see, hear, smell, touch, and taste the world.

In his journey back to the person he had been (and more, I suspect) he became aware of many lessons. He appreciated the importance of community, and hence of forgiveness – fellowship. Also, he came to recognize, with some shame, that he was seeing the dailiness of life from womens’ perspectives for the first time. From being uncertain of his role at first, learning to follow the direction of two women, he came to relish the newfound togetherness he discovered.

Everywhere in this inspiring story is the beauty there that filled the eyes and the heart.

Rebanks’ urgent questions speak directly to me and are the ones I most hear from my readers.

Because this is such an essential message for us all, I want to give you Rebanks’ final thoughts:

if we are to save the world, we have to start somewhere. We just have to do one damn thing after another. …

We all have to go to work in our own communities, in our own landscapes. We have to show up day in, day out, for years and years, doing the work. …

And we have to accept and keep the faith in each other, and somehow work together.

It feels important to me to quote extensively from the author’s own words, but in this subtle, powerful story, there is so much more. I urge you to read The Place of Tides for yourself.

** Near the end of this book, I found what I myself would most like to be:

Her poetry was her life, her work, and the depth of her love for the islands. She didn’t give a damn what anyone else thought, or whether they listened to her. Either you tuned in and became part of her world, or you remained an irritant, a jarring note. It wasn’t that she had no ego, but that she mostly forgot about it, or shelved it, when she was on the island. And in this radically pared-back life, she had found peace and meaning. She was the waves, the light, and the terns rising and falling on the bay. She was them, and they were her.