Wetlands

I’m in love all over again.

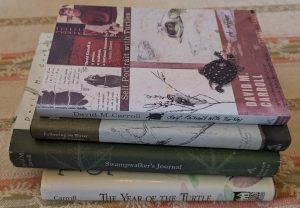

Each spring I revisit one of David M. Carroll’s outstanding wetland books: The Year of the Turtle: A Natural History, Swampwalker’s Journal: A Wetlands Year, Following the Water: A Hydromancer’s Notebook.

Even while flurries still sting my cheeks, I turn to Carroll as a gateway into the coming months when I will explore my own water meadow, marshlands and vernal pools. And I am happy to bask in his fine words, which are an affirmation of our shared lifelong appreciation of wetlands, with “a particular eye out for turtles”.

He speaks so exactly for me:

It is my delight and good fortune to have spent a large measure of my life in wetlands. For close to five decades now, from an intuitive boyhood bonding to a more scientific perspective in later years, I have moved among vernal pools, marshes, swamps, floodplains, and peatlands. Later science has done nothing to diminish earlier poetry: answers only unlock questions, and specific knowledge only deepens the mystery of the earth’s landscape and life.

I too have had the gift of many Springs, closely watching my own particular land.

This year I am turning back to my favourite Following the Water.

As it is in the book, here, for me now it is the time of the red maple flowering. It’s the in between time. Not winter. Not spring. Everywhere there is half flowing, oozing water and, for now, the special short-lived gift of vernal pools. The wild, shrill calling of peepers in the water meadow below me is almost, but not quite, unbearable. It is hard not to fall into joy at the approach of so much new life.

Not only is Carroll a winner of a MacArthur Fellows Program and the John Burroughs Medal for distinguished nature writing, he also is a fine artist, whose graceful drawings of his wetland subjects are both studies and art.

Reading Following the Water it is as if he takes me by my arm and leads me across the rough ground to his beloved place. He is sharing his treasure. As I read, he is inviting me to “enter the soul of the seasons.”

During its flood season,” he says, “ this tiny marsh, like any wild wetland, no matter what its size, is a natural theater. … Here spring is magnified in clear water lying upon land.”

So there is wonder:

I enter the dense emergent thickets of silky dogwood, silky willow, winterberry, and alder, with song sparrows singing and swamp sparrows trilling, and wade to the sun-flooded southern end of the vernal pool to look in on the islandlike masses of wood-frog eggs. In clearest water I see developing tadpoles twitching in the transparent medium from which they will be born. On the verge of hatching, they too pulse with an eagerness to move on, an innate evolutionary impatience arising from the fact that their natal water will not be here forever.

OR

Nothing is stagnant in April. Even isolated catchments tremble, as though the water in them is anxious to leap back into the air. The pool’s surface vibrates, its quivering tension shimmer with sunlight.

There are stories of mayflies, otters, yellow warblers, gray treefrogs, a gray fox, and always there is the quest for turtles. Carroll is breathing what is in my heart. How to explain it? He says through his pursuit he “enters the soul of the seasons.” I am not simply reading the book. Engaged by his mention of things more familiar than kin, I am living inside the book.

But this time I am reading with my eyes wide open to the painful acknowledgement of the human destruction of the miracles which sustain us:

I did not want to overwhelm readers of this book with laments and tirades, but each wetland I wrote about evoked vivid scenes of habitat degradation, alteration, fragmentation, and loss.

This radiant love for the land is sorrowful because of the constant awareness that the web of this miraculous life is being assailed from all directions.

As Carroll writes in the epilogue to Swampwalker’s Journal

A century and a half ago, Thoreau wrote in dismay and anger of his realization that he was attempting to read the book of nature, only to find that his ancestors had torn out so many pages.