Woman, Watching, Merilyn Simonds' Exciting Biography of Louise de Kiriline Lawrence

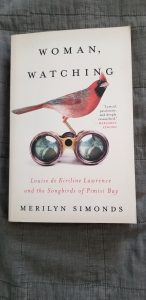

Merilyn Simonds’ fine new biography, Woman, Watching is a labour of love which not only opens a dialog into what a biography can be but also about how naturalist and author Louise de Kiriline Lawrence should be remembered. This compelling story touched me on many levels.

Merilyn Simonds’ fine new biography, Woman, Watching is a labour of love which not only opens a dialog into what a biography can be but also about how naturalist and author Louise de Kiriline Lawrence should be remembered. This compelling story touched me on many levels.

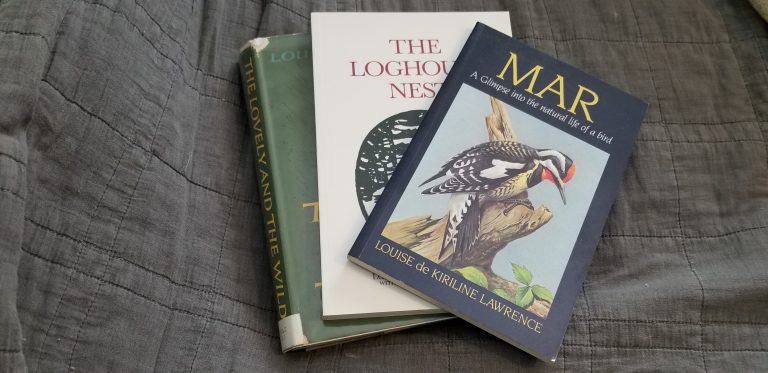

Louise and her nature books have been special to me since the days when one of my publishers, Barry Penhale, used to slip me copies of them when he came by to visit. (As a friend of Louise, her publisher and champion as well as mine, he always carried boxes of our books when he travelled around Ontario promoting them.) From those days I appreciated that her life and work would be a continuing inspiration.

De Kiriline Lawrence interested me because she was a remarkable woman who courageously lived and wrote about her most authentic life from her vantage point of what then was the north country wilds. This exceptional amateur woman naturalist in northern Ontario, banded birds, contributed important ornithological field notes. But what particularly matters to me is that she became a fine and lyrical storyteller. But there is more.

Simonds tells de Kiriline Lawrence’s fascinating background story with just the right amount of painstakingly researched detail. After growing up in Sweden in an aristocratic family where she learned to love the wild, Louise became a war time nurse. While serving, she fell romantically in love with, and married, a Russian officer who died during the war. In 1927 she left her homeland and emigrated to Canada, where she worked in health care, north of North Bay, Ontario.

Ever since the family estate of her childhood had been sold, she had held fast to the dream of finding another place of wildness which could not be taken from her. Eventually with the generous help of Len, who would become her second husband, she built a cabin on 3.45 acres.

When Len went to fight in the Second World War, leaving her temporarily free of financial insecurity, she was granted “the gift of solitude”, a gift which I also have come to know as well.

Louise had built the cabin to fulfill an ardent wish to awaken every morning for the rest of her life with the sunrise in her face, to spend her days in quiet contemplation. Now at last she was free to follow her curiosity too—and what she was curious about was the natural world.

Now she learned to observe birds closely and to record her observations in a daily bird record which continued for 42 years, and banded birds from 1942-1959. Simonds is particularly interesting picturing the hard-won evolution of this naturalist and the mentors who inspired and guided her, such as P.A.Taverner, whose aim in writing his pioneering bird-watching book Birds of Canada was

‘to awaken and stimulate an interest, both aesthetic and practical, in the study of Canadian birds.’ There was, he said, much valuable work to be done, by every sort of watcher, physiologist, behaviourist, and amateur too.

Simonds sheds light on such topics as the role of the amateurs in ornithology, who to this day continue to make significant scientific contributions, and also on the important friendships Louise developed with the few women in the field.

Occasionally Simonds interpets Louise’s behaviour by sharing similar experiences of her own, such as learning to illustrate her own bird-watching observations with sketching. These feel exactly right, never excessive. As she explains:

A biography, I decided, is a testament, proof that something exists, and so I made myself and the biographical process visible, made my efforts to observe Louise part of the record, in the same way that she documented the particulars of each watch in her observational study of a bird.

I have no delusions about my artistic talent. But I know that drawing helps me see in a different way, makes me more inquisitive about what I’m looking at, a spiral into deeper understanding. Every drawing becomes an investigation, an opportunity to grasp some elusive detail.

For me, Woman, Watching affirms my own passionate whole-hearted commitment to finding my true home and telling its story. But I have to say that for all the triumphs of Louise’s life, nevertheless it is a comfort to me that Simonds never turns away from the pain Louise experienced in avian loss, and which has only become more dire in recent years. I take comfort in reading this honest account of the anguish of living with changing nature and surroundings. Here at Singing Meadow, for example, there has been no dawn chorus for several years now. Each spring, where there were flocks now there might be only three individuals. The gaps—no more bobolinks, marsh hawks skimming the wetland, no shrike, no meadowlark, no bittern.

Also, there is an honest account of the frustration and discouragement she endured through the unhelpful publishing world of those times. These exactly match my own experience as a Canadian nature writer.

As the best biographies do, reading Woman, Watching sent me back to appreciate Louise de Kiriline Lawrence’s beautiful, deceptively simple writing. I look on her exquisite account of spring dawn in a northern woods in The Lovely and the Wild as nothing short of miraculous.

A strong and constant awareness is what I would wish for…to create in all of us, creatures of thought and reason, the attitude that would endow us with ability and sense to rediscover and to realize how infinite these systems are and just how tough and how exact a gauge is set by which each part, the largest as the smallest, the highest as the lowest, is made to work in perfect unison.

In sympathetically restoring Louise de Kiriline’s remarkable, important story Merilyn Simonds’ gift of Woman, Watching, is a treasure.